It has been almost exactly three years since Playing to Win: Raising Children in a Competitive Culture was released. And people continue to read it, which is definitely an amazing feeling. In fact, sales are up this year! Mostly this is thanks to professors assigning the book/excerpts in classes, and I can tell you that few emails are better to read than those that come from undergrads assigned to read your book sending you emails/thoughts/complaints/suggestions. So, thank you! As I teach the book myself now, and still speak to parent/school/community groups about issues related to competitive afterschool activities, I do have some things I would do differently now, if I could.

- Technology- Back when I was doing fieldwork for Playing to Win technology was an issue that I could have highlighted more. By this I mean not only the rise of iPhones and iPads, but also the role of technology in the activities themselves (websites ranking young players nationally, eliminating small ponds almost entirely) and in the college application process (both IT like the rise of the Common App which makes it easier to apply to more schools at once, and transportation technology that makes it easier to get to farther flung locales). Since I concluded fieldwork technology has only increased, making long (soccer) road trips easier for some thanks to iPads, and continuing to increase teaching and training capabilities with chess. Moreover, traditional media, but especially social media, has made stars out of young competitive dancers in a way unimaginable a decade ago. So, in short, technology would be a much bigger part of the Playing to Win story today.

- Inequality/pathways- As I've previously blogged about, I should have *explicitly* addressed inequality more. This is particularly true when it comes to the role that competitive afterschool activities play in reproducing class inequality, especially as it relates to the unequal distribution of competitive kid capital. So I would have hit that over the head a bit more. Similarly, while I say it, I needed to emphasize even more that pursuing the pathway of competitive afterschool activities is not the only way, or even required, for elite college admissions (but now nearly all the Playing to Win kids are in fact college age, and I know where some ended up, so it would be interesting to follow-up and present where they go and how they and their families think the youth activities did or did not make a difference). That said, if you are applying to these schools from areas like Wellesley, MA or Marin County, CA or Winnetka, IL, then this is likely the path you will need/want to follow. In fact your childhood family will likely have made choices similar to many Playing to Win families during, or even before, you were in grade school. I make these statements without any value judgment. Instead I emphasize that, for better or for worse, this is how the world of upper-middle class American childhood is currently organized, and the book explains how and why it is organized in this way (without suggesting ways to change it, or even if it ought to be changed). The goal is to give the reader context to make their own decisions and create an informed opinion.

- Advice to parents- All that said, many readers/audiences *do* want more advice, and practical advice at that. For instance, how to decide on a particular competitive afterschool program, or coach? Or, when to know it is time to stop? I have not only informed opinions here, but also some answers drawing on research outcomes by both myself and others. So I likely would add more of that in an updated conclusion, even if it's not "traditional" in an academic book. It would build on my "buffet" approach. Or, you could just invite me to speak to your group to learn more. ;)

It has been interesting to see how all the Playing to Win issues are beginning to play out in my own life now that I am a parent (when the book came out I was expecting #2). My now 4.5-year-old has sampled all three of the Playing to Win case studies (and then some).

- Chess- This is probably the most "us" activity in my family unit. When I posted that Carston had started chess on Instagram I wrote, sincerely, that, "For anyone who knows us, that this is happening is perhaps 0% surprising."

I would still not say that he is really playing chess, but he knows how the pieces move and he is making an attempt. Carston really likes games and puzzles, and has good spatial awareness, so this could be a good fit.

That said, I know how much work you have to actually put in to be good at chess, even at young ages, and unclear if that will be in the works. At the moment he only plays with his instructor, never with a parent. Soon hopefully he can play with other kids and perhaps in kindergarten play in some non-rated tournaments and see how he likes it (especially given that he is the child who WAILED after losing Chutes & Ladders, a game which I explained is almost entirely due to chance).

- Dance- This has been a much more textured experience thus far. He actually did a dance class and recital last year, before we moved to Rhode Island. The recital wasn't a very positive experience because he didn't feel very prepared (they started the routine about a month before the recital, which doesn't work great with 3-year-olds!). Also, even at the recital, the littles didn't perform until after intermission, which meant sitting through a lot before their turn. But when we moved to Rhode Island I knew that there were several great dance studios in the area. I did quite a bit of online research watching videos (for technique), reading teaching philosophies, and looking at schedules/curriculum. I was very happy with the studio I settled upon and he generally had a great experience in a tap/ballet combo class. I especially loved that the dance studio doesn't have observation windows and only allows parents to observe twice per year (this is part of that practical advice I mentioned above that I give- I tell parents do your research BEFORE you sign up, and then step back and let the teacher/coach/program handle the instructing because chances are very slim you actually know more about instructing/teaching little people in a particular activity). Here he is at the second observation in the spring.

I noticed one particular mom at the observation week. She had brought in a high quality camera and sat off a bit by herself (a few seats down from where most of the other moms had clustered in the chairs in the center of the room). When it came time for the kids to "perform" what they had learned already of their recital routine, this mom got very agitated. I saw her go up to her daughter and say something, and then (keyed to her at this point with my fieldworker hat on and not my mom hat) heard her hiss from her seat, "You know this! Why aren't you doing it right?!" Nothing so out of the ordinary unfortunately in a lot of kids' activities, but not someone I'd want to hang with as a mom.

When it came time for the dress rehearsal I noticed both she and her daughter weren't there, but thought maybe they had left the class/studio. But lo and behold on recital day they were there. Oh, yes, they were there.

Again, the camera was around her neck (I was a backstage mom mainly because Carston was the only boy-- more on that in a few) and she was backstage to try to get good snaps, not to help the kids (in fact I took her daughter to the restroom before the performance as she was positioned in the wings already). In any case, when they went out to perform of course the kids were a tad overwhelmed by the stage lights and audience. They had a helper who tried to get them into their line-up spots as quickly as possible. This little girl-- I'm sure partly because she missed dress rehearsal-- was late to her spot and confused at the beginning. Her mom, beside me in the wings, starts saying, "Someone has upset her! Oh, GREAT, now she's not going to do the routine the right way!" She kept going on and on and I finally said, "They are adorable, and they are only 4-6 years old, it's no big deal!" Needless to say she walked away from me to a wing further upstage where she proceeded to stage whisper at her daughter! By the time they finished the routine (which they ALL did admirably for their age) the little girl came offstage in TEARS.

Now, I have been to about 20 child beauty pageants. I have been to more dance competitions than I can count. I have been to double-digit chess tournaments where tears happen all the time. But I never saw something like this. Instead of comforting her crying daughter this mother stalked off with other kids from the class. It was deliberate and it was cruel. I tried to comfort the little girl, while telling all the kids (including mine!) that they did a great job. The mom finally took the girl off on her own. Poor thing.

Note I say all the other little girls, because my guy was the only guy in this class. He's started to notice things like this a bit more, but it still doesn't really bother him. About halfway through the year he told me he didn't want to keep doing dance though. We talked about it and he mentioned the "girls" weren't friendly to him (which I am guessing was some combination of being a boy, being a touch younger, and not going to school with any of them), which I didn't quite believe. Note every time he actually went to class he was happy. But on his own he came up with a compromise, "I will do the recital, but after that, no more dance." I agreed that made sense.

Then the dress rehearsal happened. Now first of all, you can't tell me this isn't a little guy who wanted to be there:

At the dress rehearsal they had some trophies out. Those gold, somewhat cheap and tacky, trophies I write about in Playing to Win. And my child was SEDUCED by them. "Mommy, how do I get that?!" We asked the studio owner and she explained that after you do five years of recitals you can earn one of those trophies. To which he immediately declared, "Ok! I am going to do five!" I said we would talk after the recital. And sure enough he said he did want to keep dancing this year. So he'll be back in a combo class and we will see what happens... But it blew my mind to see the trophy culture up close and personal and see how effective it can be with little kids.

At the dress rehearsal they had some trophies out. Those gold, somewhat cheap and tacky, trophies I write about in Playing to Win. And my child was SEDUCED by them. "Mommy, how do I get that?!" We asked the studio owner and she explained that after you do five years of recitals you can earn one of those trophies. To which he immediately declared, "Ok! I am going to do five!" I said we would talk after the recital. And sure enough he said he did want to keep dancing this year. So he'll be back in a combo class and we will see what happens... But it blew my mind to see the trophy culture up close and personal and see how effective it can be with little kids.

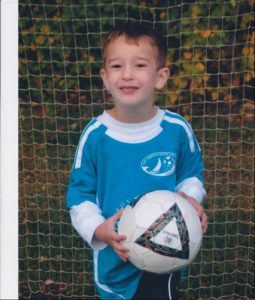

- Soccer- Of the three Playing to Win case studies this has been the least successful by far, especially for my older son. Again, before we moved to Rhode Island, he had tried soccer. But the soccer he did was a class in a gym, not outside on a field trying to work with teammates. He started off the "season" super psyched.

(If you read this blog regularly you may remember my post last year about what to do about those pink shin guards...)

(If you read this blog regularly you may remember my post last year about what to do about those pink shin guards...)

And the first practice was a success:

But things quickly unraveled for two reasons. 1) My child (much like his mother) doesn't love being cold. And when the weather turned his attitude turned as well. Not much to do about that with a 3-year-old... 2) More significantly, the "coach" of his team was not very engaged. He never once referred to the kids by their first names-- in fact, I'm not even sure he ever knew them. That just doesn't fly with 3-year-olds. He knew about soccer, but not how to instruct such young kids. The "head" coach for the little ones did have great energy and activities, and when Carston had him he liked soccer much better.

But things quickly unraveled for two reasons. 1) My child (much like his mother) doesn't love being cold. And when the weather turned his attitude turned as well. Not much to do about that with a 3-year-old... 2) More significantly, the "coach" of his team was not very engaged. He never once referred to the kids by their first names-- in fact, I'm not even sure he ever knew them. That just doesn't fly with 3-year-olds. He knew about soccer, but not how to instruct such young kids. The "head" coach for the little ones did have great energy and activities, and when Carston had him he liked soccer much better.

But this reminded me of advice I give to others: Always ask *who* will be working with your child. A program might be great, but if you don't know who will actually work with your child, no guarantees. Many think it will be "easy" to work with the youngest kids, but it's actually quite a different skill set to do it well.

Following advice I also give others-- to stick with the commitment you made but not recommit if your child hates something-- we aren't doing soccer again this year. Until very recently whenever I asked he adamantly said he didn't want to do soccer. His interest is (only slightly) piqued again post-Olympics, but I decided that better to take a year or two off and then try again so he doesn't completely sour on it. Because honestly this "official team photo" pretty much sums up how it ended:

If anything my challenge with my eldest son is that in general he likes/wants to explore and try most everything. I have to resist overscheduling him for sure. He also does swim lessons (mainly for safety purposes, NOT because we have dreams of Phelps-ian glory), gymnastics and karate for a "sport" (and I would think in the next year or two we'll have to choose between these two as they are similar in terms of being a solo physical activity-- though not surprisingly he's super into the different colored belts/stripes he can earn), and music lessons. I've surprised myself by how Tiger Mom-ish I am when it comes to the music. He did a Suzuki sampler class last fall and himself chose (unexpectedly!) the cello after trying violin, flute, guitar, and piano. I need to read some of the Suzuki texts more closely (more to come!) but it is *significantly* more expensive than other activities so I feel like we need to really do it "right." I have mixed feelings about the parent needing to be in the room, which is part of the reason I need to read up more on this. Here he is trying out a new, larger cello for this upcoming year's lessons:

If anything my challenge with my eldest son is that in general he likes/wants to explore and try most everything. I have to resist overscheduling him for sure. He also does swim lessons (mainly for safety purposes, NOT because we have dreams of Phelps-ian glory), gymnastics and karate for a "sport" (and I would think in the next year or two we'll have to choose between these two as they are similar in terms of being a solo physical activity-- though not surprisingly he's super into the different colored belts/stripes he can earn), and music lessons. I've surprised myself by how Tiger Mom-ish I am when it comes to the music. He did a Suzuki sampler class last fall and himself chose (unexpectedly!) the cello after trying violin, flute, guitar, and piano. I need to read some of the Suzuki texts more closely (more to come!) but it is *significantly* more expensive than other activities so I feel like we need to really do it "right." I have mixed feelings about the parent needing to be in the room, which is part of the reason I need to read up more on this. Here he is trying out a new, larger cello for this upcoming year's lessons:

No need to start referring to me as Hilary Chua quite yet though... In the meantime, I get to start all over with my youngest son, Quenton, as he starts exploring the Playing to Win activities, and more!