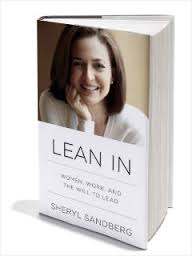

So much ink has already been used up discussing one of the hottest books in recent memory, Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In. For that reason I was hesitant to add my two cents, even though I had many thoughts while reading the book (Not the least of which was, "Wait, I feel like I do all this, so why am I not Sandberg?!" Although, I still have nine more years to become the fifth most powerful woman in the world I suppose...). But I realized that I hadn't read some of things I was thinking, so I wanted to share. The below piece, originally published on The Huffington Post, focuses on single-sex education as one way for young women to learn how to lean in. I also want to add that I found it pretty egregious that Sandberg didn't discuss Larry Summers' 2005 remarks on women and science. I understand that he is her mentor, but it just screamed out to be addressed. I suppose it's yet another example of why women need to lean in, but I would have appreciated hearing her perspective on the incident (more than knowing that the incident with her children and lice occurred on a private jet as opposed to commercial aircraft-- since the private part didn't really matter for her overall point).

Most of my other thoughts (besides my own personal anecdotes and experiences) have been addressed by others far more eloquent than yours truly. But I'd love to hear what you think, so feel free to leave me a comment here or on Facebook/Twitter!

When people find out I'm the product of eight years of all-girls' schooling they often ask what the best part of the experience was. I usually answer, only half-joking, "I rarely had to shave my legs."

Lately I've been thinking more seriously about my single-sex education after devouring Sheryl Sandberg's now infamous Lean In. One of Sandberg's bigger points is that a lot of work needs to be done long before women are in careers, graduate school, or even college, in order to teach them how to lean in. Given this focus on childhood and adolescence I'm surprised that all-girls' schools haven't been discussed in the same breath as Sandberg's long-term project. Based on my experience, and my research on competition, gender, and education, promoting all-girls' education in the grade school years is a useful strategy to raise women who know how to lean in throughout life.

In Lean In Sandberg explains that as a child she used to organize all the neighborhood children and tell them what to do. But to this day she cringes when her siblings tell this story because: "When a girl tries to lead, she is often labeled bossy. Boys are seldom called bossy because a boy taking the role of a boss does not surprise or offend."

My professional, adult self certainly understands this sentiment, but my 13-year-old self would have been confused. At 13 I would have said that of course girls need to be bossy -- who else would lead? I always thought of girls as the sports stars and the valedictorians, because at my school they were.

I took this attitude with me into high school, a building that sat next to an all-boys' school. Some of my classes were coed. The boys came over for European history and drama, classes where I always positioned myself in the front row, preferring the "visiting" boys sit behind me. To my teenage self they were clearly infringing on my territory and I made sure I outperformed them. That confidence translated when I went next door for Latin, where I righteously covered my tests with my arm to make sure the boy sitting behind me couldn't cheat off of me (a trick he only got away with once).

When I arrived at Harvard (also Sandberg's alma mater) I was never afraid to raise my hand in a seminar, and I quickly learned that the best way to be heard meant jumping into the discussion and not waiting to be recognized. I credit my earlier classroom experiences for my chutzpah.

But being a social scientist I can't help but look to the literature (incidentally, the well-researched footnotes are one of Lean In's strongest features, and worth a read), and that's when the picture becomes more complicated. A 2009 study by professors at UCLA's Graduate School of Education & Information Studies presented data that graduates of all-girls' schools show stronger academic orientations, especially in math and computer skills, and higher standardized tests scores, than their coed counterparts. Other studies have acknowledged that all-girls' education doesn't necessarily improve academic performance, but they haven't found that it hurts either. A well-publicized 2011 Science paper disagreed, proclaiming that single-sex education can have a long-term negative effect by promoting gender stereotypes.

CLICK HERE TO KEEP READING ON THE HUFFINGTON POST BOOKS!

Short of being able to do twin experiments (where one identical twin goes to a coed school and the other goes to a single-sex school), we may never know the precise effect of what learning in a single-sex environment does for girls. But we can know how people assess their experiences -- like me and my former classmates.

Thanks in part to Sandberg and her Facebook team, I know that many of the girls I attended middle and high school with have made a variety of different choices as women: some are married, many have children, and some are stay-at-home moms while others are doctors or lawyers (one even premiered at the Metropolitan Opera this month, while still nursing her five-month-old son). We all learned as young women the hard-to-measure notion that females can be leaders in any area just by looking around us at our peers. This knowledge and the confidence that comes with it can't be discounted.

And while we're at it, ladies, it's also worth remembering that shaving your legs every day isn't a necessity -- and not doing so leaves more time for all kinds of leaning in.