Please note that this was syndicated on BlogHer on April 8, 2010: http://www.blogher.com/mommydaddy-it-hurts. Check it out! April is National Youth Sports Safety Month, according to the National Youth Sports Safety Foundation (NYSSF). I've been thinking a lot youth sports injuries-- last week I presented some preliminary findings from my research on youth sports injuries and the relative-age effect (which is joint with Rebecca Casciano and Children's Hospital Boston). One of the NYSSF's "Tips for Athletes" is especially relevant: "Some children grow faster than others and some have better coordination earlier than others. Everyone catches up eventually. Be patient."

I've mentioned my interest in age cut-offs here before, but today I want to highlight a different set of findings about how parents deal with youth sports injuries, which are especially timely. Last week Gatorade released a study of "Sports Moms," a group they estimate is about 13 million strong. Based on a poll of 900 mothers of middle- and high-school age athletes, Gatorade reports that these sports moms spend more money on, and time with, their kids than parents whose children don't play sports. To do so they sacrifice their own personal time like sleep, exercise, and leisure.

It's not at all surprising that Gatorade chose to focus on sports moms, as they tend to be more involved in children's afterschool lives. Dads are getting more involved, especially with girls and sports and coaching, but for the most part moms are still the ones who do the "dirty" work of washing uniforms and schlepping to and from practices. I've always thought that the title of this book, by an Australian academic, pretty much sums it up: Mom's Taxi: Sport and Women's Labor.

So it didn't surprise us that moms were much more likely to be with kids when they visited the doctor for a youth sports injuries. What did surprise us is how many dads were present as well. Out of 989 office visits, dads were at the appointment 44.7% of the time.

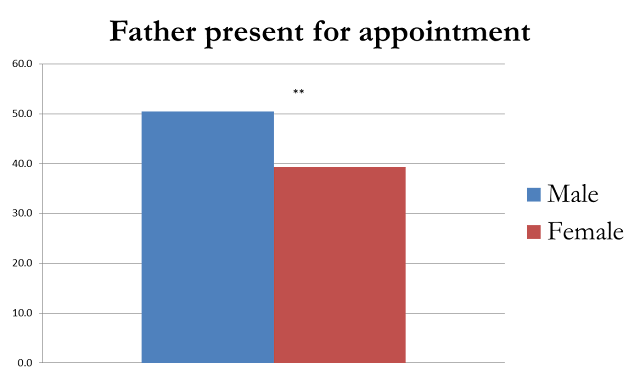

However, dads are significantly more likely to be at an appointment if it is their son who is injured, irrespective even of a child's age.

(Note that there are more injured girls in our sample-- 54.3% of 2291-- which is higher than expected based on the sex ratio for girls this age born in the state of Massachusetts).

We have several possible explanations for this, but I'm interested to hear your thoughts! Is it that dads are simply more invested in their sons' athletic careers, or that boys play sports that are more likely to interest men (unlike, for the most part, the girls who dance, do gymnastics, or figure skate)? Other thoughts?