While most of us spent yesterday celebrating fathers we seem to spend the rest of the year placing parents under a microscope. So far in 2012 we've heard about why French parents are superior and why you aren't good enough if you aren't a breast-feeding mom. And those are just the major headlines. Yesterday The Boston Globe Magazine ran an excellent piece on spanking, along with a well-researched timeline on the history of discipline in Massachusetts (though I do wish they had defined "spanking" more clearly-- is it over the clothes, using a strap, etc.). The author, James Burnett III, starts by explaining how closeted spanking is and how many parents would not even consent to be interviewed. He even compares the shame associated with spanking to extended breastfeeding.

This feature was especially timely given another story that made the rounds last week: Mom Carla Williams, of Lowell, MA was arrested after punching her 10-year-old daughter in the nose. Williams claimed that she could discipline her child any way she saw fit. The law disagrees, of course. In a TV appearance on NECN's Morning Show and a radio appearance on WBZ's NightSide last week I explained why Williams is wrong-- mainly because you should think of discipline as child abuse if you bruise, break bones, or draw blood. You can see my clip below, and read more of my thoughts which are part of the article on their website, "Fallout after Lowell, Mass. mother accused of punching her child."

Both discussions were framed around the challenging question of whether or not we should license people to be parents. This would be difficult for all sorts of legal and historical questions, as I mentioned, but it is worth pointing out that there is one instance where we do in fact require parents to be licensed: adoption. Adults who want to adopt go through a rigorous process to prove their worthiness and capabilities. In many instances age (at the upper bound), sexuality, race, education, and class come into play and worthy people are dismissed. These are people who would more than likely make excellent parents if they could conceive on their own. They would almost certainly be better parents than Carla Williams and Tuan Huynh, a Pennsylvania father who was recently sentenced for abandoning his 16-year-old daughter 14 miles away from her home after she failed calculus. Huynh, who clearly wants the best for his daughter in terms of her education, didn't have the best parenting education himself; now he'll have to take parenting classes that clearly would have been helpful before this tragic incident.

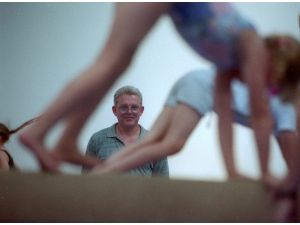

Also, as more and more details of abuse emerge from the ongoing Jerry Sandusky trial, it's worth remembering that youth sports coaches also don't have to be certified to work with kids (Note that I wrote in that piece, "Sadly, nail salons are better regulated and have more safety requirements than programs where children can suffer catastrophic physical and emotional injury." In Sunday's New York Times Magazine Jacob Goldstein wrote an interesting article on efforts to loosen restrictions on cosmetology licenses in various states. A diverse group are backing these efforts, which this far have not been successful. I wish more would focus on licensing those who work with children and worry less about licensing or not licensing those who braid hair). As long as children are accused of "asking for" sexual abuse, as this story about an Indiana high school student who was raped by her volleyball coach suggests, it's clear we need better education not just for kids and coaches, but for parents as well.

No parent is perfect and we all can use more knowledge and education. But no adult should abuse a child in any way and legally get away with it. No matter what their credentials say.