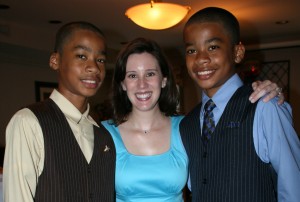

I have a soft spot for scholastic chess. In 2005 I started studying chess as part of my dissertation research (which is forthcoming as Playing to Win: Raising Kids in a Competitive Culture). One of the things I loved the most about the chess scene is the diversity of people who meet and engage over the board. At many tournaments you can walk in and see men, women, boys, girls, whites, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, rich, poor, young, and old shaking hands before their games... And then shaking hands at the end again, before retiring to the "skittles rooms" to analyze one another's moves. It's really a beautiful thing. I already can't wait for my husband to teach our son "how the pieces move." During my time exploring parents' motivations for enrolling their then-elementary school-age kids in chess tournaments I met many wonderful families and kids. It was a particular thrill recently to see one of these "kids" (who is really almost a man) written up in The New York Times for his chess accomplishments. Jehron Bryant is now 15 and he was recently named a chess master. His current chess rating is a remarkable 2219 (and I'm guessing he'll soon perform higher than that number when he takes his SATs, for which I know he has been studying). What's even more remarkable is that Nigel, Jehron's twin brother, is also close to becoming a chess master, with a rating of 2099.

Nigel and Jehron are part of a remarkable group of African-American chess-playing teenagers in the New York City area, Dylan Loeb McClain explained in his article. Three other teens-- Justus Williams, Joshua Colas, and James Black, Jr.-- became masters before their thirteenth birthdays. Why is this so remarkable? A quote from grandmaster Maurice Ashley (the first black GM, and only African-American GM) sums it up nicely: "Masters don’t happen every day, and African-American masters who are 12 never happen... To have three young players do what they have done is something of an amazing curiosity. You normally wouldn’t get something like that in any city of any race.”

While there is much to love and applaud in the scholastic chess world, there has also been recent tragedy. A few weeks ago, at the National K-12 Championships held in Dallas, another young chess player of color, and of great potential, died unexpectedly. Quinton Smith was a junior at Estracado High School in Lubbock, Texas. He was one of two representatives from his school; they only had money to pay for two of their eighteen students to attend nationals and Quinton won his spot after an intrasquad tournament. In addition to being part of the chess team, Smith was on the mock trial team, the tennis team, and involved with the drama club.

Quinton Smith's death was officially designated as "unexplained." After losing his first four games, and taking a bye for the fifth game, he appears to have gone up to the roof of the hotel and either fallen or jumped. No one seemed to know how he got up to the roof. Dr. Daaim Shabazz's entry on The Chess Drum offers a particularly sad description of what occurred. I'm not the only one to think this was likely a suicide, though I couldn't find any verified reports online. Chess teacher Elizabeth Vicary wrote on her blog: "I assume his tournament performance had something to do with his death: that he was used to being smart and successful and just couldn't take the frustration and pain of so much losing." Vicary used the opportunity to talk about how to make decisions and recover from mistakes/errors with her own students.

Just as all competitive endeavors can bring the joy of victory, they also bring the agony of perceived failure. For most kids learning to deal with loss, and learning how to recover, is an important life lesson/skill that they can acquire by participating in a variety of competitive activities, like chess, as I've written about before. But for a small group, this lesson may be too much to take-- especially if they have become accustomed to success. Unfortunately it seems as if Quinton Smith may have fallen into this category. Hopefully parents and teachers/coaches can learn from this tragedy how to better identify kids who may wilt in the hothouse of competition and give them special attention or ease them into larger competitive endeavors.