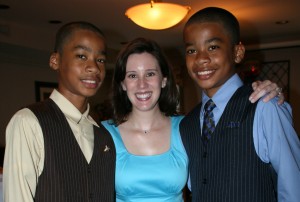

It's always great fun to see visual depictions and analysis of activities I've studied. Unlike Dance Moms, the drama in the recent documentary Brooklyn Castle isn't manufactured. It brings an important story, and activity, to a broader audience-- in a way not done since the 1993 movie Searching for Bobby Fischer. Below is my review of the documentary, originally published on The Huffington Post as "Cheering for a Mate in Two", but I wanted to add a few other thoughts. Chess is one of the three competitive activities I studied for my dissertation (and now FORTHCOMING book!), Playing to Win. I actually met two of the stars of Brooklyn Castle when they were still in grade school. I've written about the Bryant twins (and Justus Williams, who is also a focus of Brooklyn Castle) before, but here I am with them the summer we first met. Hard to believe they are now thinking about college.

I wanted to quickly highlight some things in Brooklyn Castle that might surprise you, and say that these are totally consistent with all my research on scholastic chess. These include seeing kids cry at tournaments, noticing that most of the kids have little to no desire to be professional chess players and instead want to be doctors or lawyers or involved in business, observing that most of the kids are scared to lose their ranking and rating (especially in a public way) and that this is especially true when it comes to competing against a teammate and not a total stranger, and noting that while it shouldn't matter how much money you have when you play chess resources clearly matter in terms of keeping kids off the streets and getting them access to the best coaches. All of this is competitive kid capital in action.

CLICK HERE TO READ OVER AT THE HUFFINGTON POST!

You might not know how to play chess. Or you might think chess is boring. But that shouldn't stop you from seeing a documentary about some special middle school kids who are pretty good competitive chess players and anything but boring.

Brooklyn Castle features a group of students and their teachers at I.S. 138 in Brooklyn. Approximately 65 percent of 138's students live below the federal poverty line. But the school offers them the opportunity to pursue about 45 different activities afterschool. One of those activities is chess.

And pursue chess they have. The school has won more national championships than any other junior high in the country. In fact, last year they became the first middle school team to ever win a high school championship.

Brooklyn Castle follows the school's chess club for one year, from spring 2009 to spring 2010. Students come and go but the supportive teachers and administrators remain the same. Over 100 kids vie for a spot to represent 138 at state and national championships; the team roster shrinks during the course of Brooklyn Castle thanks to the economic crisis and subsequent school budget cuts. It's serious stuff, but the filmmakers have made the students' and teachers' reaction to all the dramas entertaining.

Despite financial setbacks the students achieve a variety of personal and team goals both on and off the chess board. Eighth grader Pobo runs for school president and another eighth grader, Alexis, studies for the exam he must do well on in order to be accepted into a selective public high school. Eleven-year-old Patrick has more personal goals, like earning a high enough rating to represent his school at a chess tournament, which is particularly difficult for him given his ADHD.

In many ways Patrick is the most intriguing subject in Brooklyn Castle because he was the only one of the five featured students portrayed as a true underdog. While we are often told that the kids of I.S. 138 are poor and that the school faces serious budget cuts, what we see is slightly different. In the end the school finds a way to send its top players to multiple events throughout the year that require travel and hotel stays. These kids are coached -- sometimes privately -- by Grand Masters, an opportunity thousands of young chess players would relish. Alexis, whose immigrant family isn't well-off, is shown studying for that selective high school test with a prep book. Even if his family did not buy the book and it was donated, Alexis has access to a resource that tens of thousands of NYC students simply don't have. Because Patrick isn't one of the top players on the team, like Alexis and Pobo, he doesn't get as many extras and he has to look to fellow student Pobo to "coach" him to help achieve his chess goals.

Other documentaries have shown how young students cope with differential access to resources in competitive settings in more nuanced ways. 2002's Academy Award-nominated Spellbound focuses on middle school kids like those in Brooklyn Castle. In Spellbound we see a range of experiences from across the country -- from the West Coast kid whose dad pays people to pray for his son during the Bee to the East Coast girl who lives in one of the worst areas of D.C. -- and the ability to compare gives the viewer an appreciation for what each individual student accomplishes in the finals. Another documentary, Mad Hot Ballroom (shortlisted for a 2005 Academy Award), focuses on competitive ballroom dancing in the New York City public school system among elementary school students. Both Brooklyn Castle and Mad Hot Ballroom have similar messages in terms of the need to fund afterschool programs, but Mad Hot Ballroom never explicitly lays out the need to support the arts in schools the way Brooklyn Castle does. The economic climate has certainly changed since 2005, and film-goers have become accustomed to numbers and statistics in documentaries about education (as in 2010's Waiting for Superman [for my review click here]), but the understated yet clear message in Mad Hot Ballroom may have been even more effective in Brooklyn Castle.

The best spokesperson for the importance of chess is 138's chess coach, Elizabeth Vicary Spiegel, arguably the breakout star of the film. Spiegel's calm eyes, but energetic coaching and teaching style, make you wish you had a teacher like her in middle school. Spiegel cogently explains how chess can impact children's lives by teaching them particularly lessons -- like learning how to think through problems, how to be patient, how to make a plan, etc. She is shown supporting not only her top players, but also her weaker players, like Patrick. Spiegel appears to be able to zero in on what each student needs to work on both on and off the board to help them succeed in the present, and hopefully in the future as well.

We need more coaches and teachers like Elizabeth Vicary Spiegel in classrooms across the country. We need more characters like her on film. And, we need more films like Brooklyn Castle. This documentary is better than almost any reality television show on related children's activities (like dance or beauty pageants) because of the serious tone with which it treats its subjects. Even if you don't know how to play chess, trust me, and check out Brooklyn Castle. You'll find yourself cheering for a mate in two despite yourself.